By John Titus

INTRODUCTION

The “novel” coronavirus pandemic marks the greatest turning point in U.S. monetary history since the creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913. The Virus Pandemic and the Federal Reserve are fascinating historical figures for many reasons, starting with the deceptions their very names work on the public. “Federal” Reserve falsely implies that “the Fed” is an agency of the federal government when in fact it is a cartel of 12 private banks1 acting in concert from different locations to skim interest payments off the top of the U.S. money supply in perpetuity. “Coronavirus pandemic” deliberately misdiagnoses the real disease at the root of the current crisis, which is not in fact any virus (hint: it has a 99+% survival rate) but rather a radical plan for the eventual takeover of the U.S. monetary system by the privately owned Federal Reserve.

The popular notion that a virus is the original force behind the current downturn doesn’t stand up to serious scrutiny. It’s easy if not trivial to look at a timeline of monetary events and see that the official monetary response to the “coronavirus pandemic” went into effect before there even was a pandemic. This means that the monetary “response” wasn’t initiated by any virus, but by something else. As it turns out, that something else was a radical monetary plan handed to the Fed for implementation six months earlier by BlackRock. Yes, that BlackRock—the one that had a central role in the Fed’s monetary “response,” which in actuality was nothing more than the execution of BlackRock’s plan.2

To put it bluntly, the actions taken by the Federal Reserve starting in March of 2020—actions that represented a massive departure from the Fed’s responses to crises before that time3—are exactly what BlackRock told the Fed to do in Jackson Hole, Wyoming over half a year before the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a pandemic. It was in August 2019, months before the first coronavirus story broke, that BlackRock instructed the Fed to get money into public and private hands when “the next downturn” arrived—which as luck would have it occurred less than a month later.

In a nutshell, this was BlackRock’s “going direct” plan,4 and what we are going to see here is how the Fed began executing—quite successfully—that plan (which enriched billionaires) before the pandemic was declared. The WHO’s declaration of the pandemic in fact coincides to the day with the Fed’s shifting BlackRock’s plan—already up and running—from mid-gear into high-gear, as the WHO had just armed the Fed with a huge cover story, the perfect distraction. Indeed, the Fed’s execution of BlackRock’s plan had shifted from low- to mid-gear a couple of weeks earlier, when the stock market plummeted following four months of trouble in the U.S. bond market.

The virus pandemic cover story thus permitted the Fed to kick the BlackRock plan into high gear with a massive and wholly unprecedented asset purchasing spree. But for the Fed, hyper aware of publicity as it is, the pandemic cover story came with a downside, which was that it had to actually do something to prop up the appearance of helping the public (which was and still is suffering badly under lockdowns).

In an effort to minimize that downside, the Fed came out with a rash of emergency measures that amounted to a handful of peanuts next to the trillions it was gifting billionaires. Those emergency measures arrived very late and were infected with admitted conflicts of interest at that. But those peanuts did buy the Fed some good press and enabled it to ride on the coattails of the Small Business Administration, which is where Main Street got real assistance—not from the Fed’s hackneyed jawboning.

To be clear, the Fed absolutely needed the 24/7 hype over the alleged pandemic as superficial justification for its massive $3 trillion balance sheet expansion, which in turn created $3 trillion of new money in private hands—exactly as BlackRock’s plan called for.5 Without the saturation air cover that the Fed had, its acts would’ve amounted to a naked money grab, which as it was even Jim “Mad Money” Cramer called one of the greatest wealth transfers in history.6

In actuality, as we shall see, the Fed only got around to its real plan for the public after its billionaire-enriching asset buying binge was all but over. Ultimately that plan is going to birth central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), which will give the Fed even more control over the U.S. than it has seized during the two-weeks-to-flatten-the-curve pandemic that goes on forever.

Once CBDCs go into effect, however, the Fed will soon discover that the next victim in the progressive game of centralized monetary control is none other than the Federal Reserve itself, which would be a good thing if its victimization could occur without taking the U.S. down with it. But that is another episode.

ANALYSIS

Set forth below is an analysis of the tectonic monetary shift under cover of the pandemic. Ultimately it’s the story of the Fed’s increasing degree of political control on behalf of an unelected financial elite.

A. August-September 2019: BlackRock’s Plan for “the Next Downturn,”

Followed by That Next Downturn One Month Later

Every year, 120 of the top global figures in finance, about half of whom are central bankers, meet in in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, to discuss current events and plans for the road ahead. See “Players List.”

In 2019, on August 22 to be specific, BlackRock presented at this event a radical policy “proposal” for “dealing with the next downturn” (which is the actual title of the paper BlackRock delivered there). The proposal sets forth some rather pointed advice to the Federal Reserve about how it should respond to the next crisis, namely, by “going direct.” BlackRock itself recognized and called attention to the fact that its going direct plan represented a break from all prior Federal Reserve crisis responses:

An unprecedented response is needed when monetary policy is exhausted and fiscal policy alone is not enough. That response will likely involve “going direct”: Going direct means the central bank finding ways to get central bank money directly in the hands of public and private sector spenders. Going direct, which can be organized in a variety of different ways, works by: 1) bypassing the interest rate channel when this traditional central bank toolkit is exhausted, and; 2) enforcing policy coordination so that the fiscal expansion does not lead to an offsetting increase in interest rates.

An extreme form of “going direct” would be an explicit and permanent monetary financing of a fiscal expansion, or so-called helicopter money. [Bolds in original]

What made BlackRock’s “going direct” plan for the Fed unprecedented was the part about getting “central bank money directly in the hands of public and private sector spenders” in a way that represented a “permanent monetary financing of a fiscal expansion.” BlackRock even proposed a “permanent monetary financing of a fiscal expansion.” In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed had of course embarked on a path of “quantitative easing” (QE), but under that version of QE, central bank (public) money had gone directly into the hands of the public sector spenders, meaning that reserves created by the Federal Reserve stayed entirely within the Fed’s banking circuit, i.e., among those parties who do their banking with the Fed: commercial banks, foreign central banks, and the U.S. government.

What BlackRock was now proposing at Jackson Hole in 2019 with its “going direct” formulation was to expand the 2008 version of QE to add “private sector spenders” to the list of “public” parties who received money under QE previously, and to do so on a permanent basis.

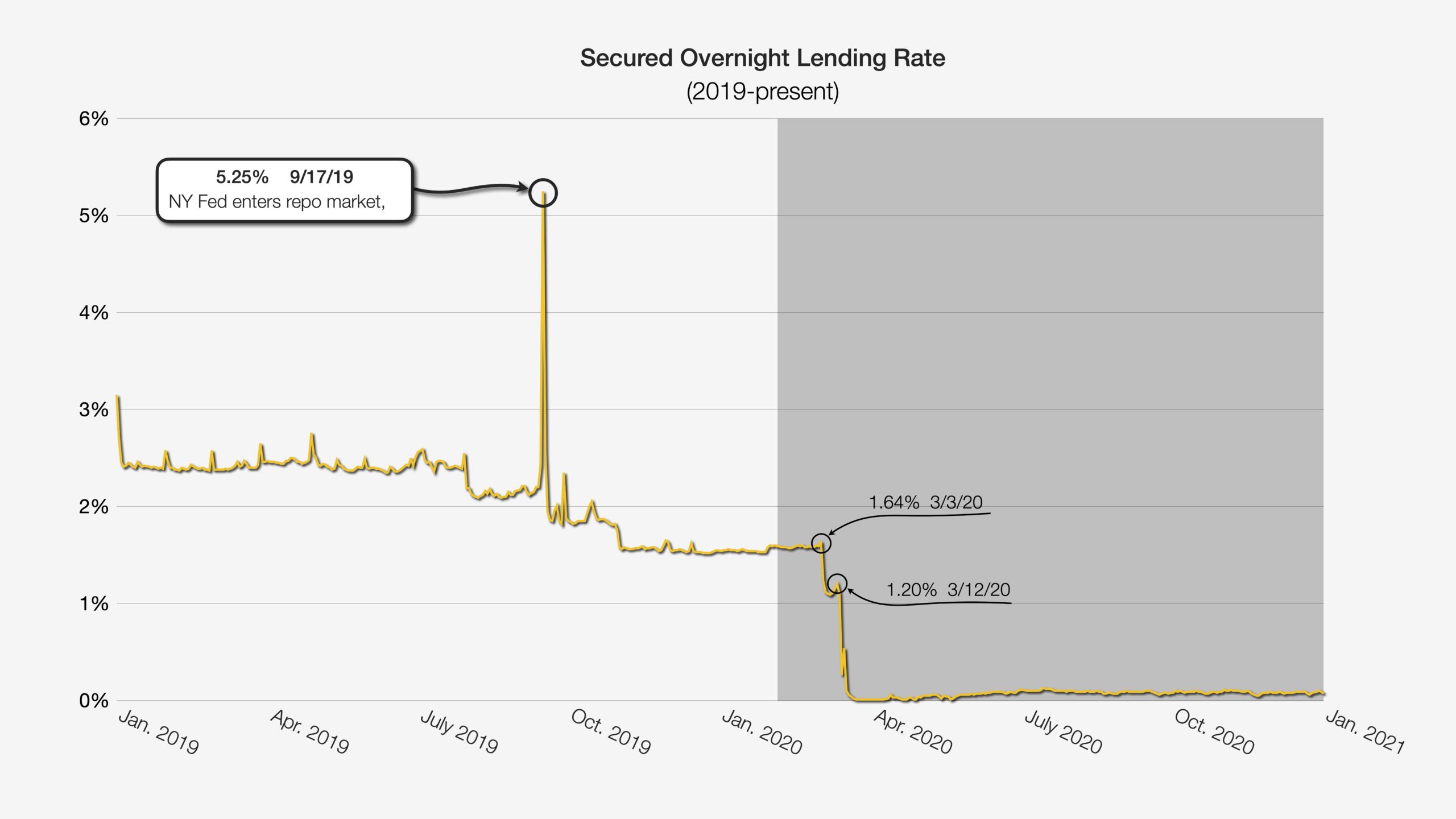

Which is exactly what happened over the course of the next year. More immediately, though, “the next downturn” contemplated by BlackRock on August 22, 2019 arrived on September 17—less than one month later. That is when the secured overnight lending rate briefly hit 10% and prompted the New York Fed to enter that market and to create new reserves to sell to borrowers eager for liquidity. See chart, “Secured Overnight Lending Rate.”7

B. September 2019-March 2020: The Fed Responds to the Downturn by Starting to

Implement BlackRock’s “Going Direct” Plan

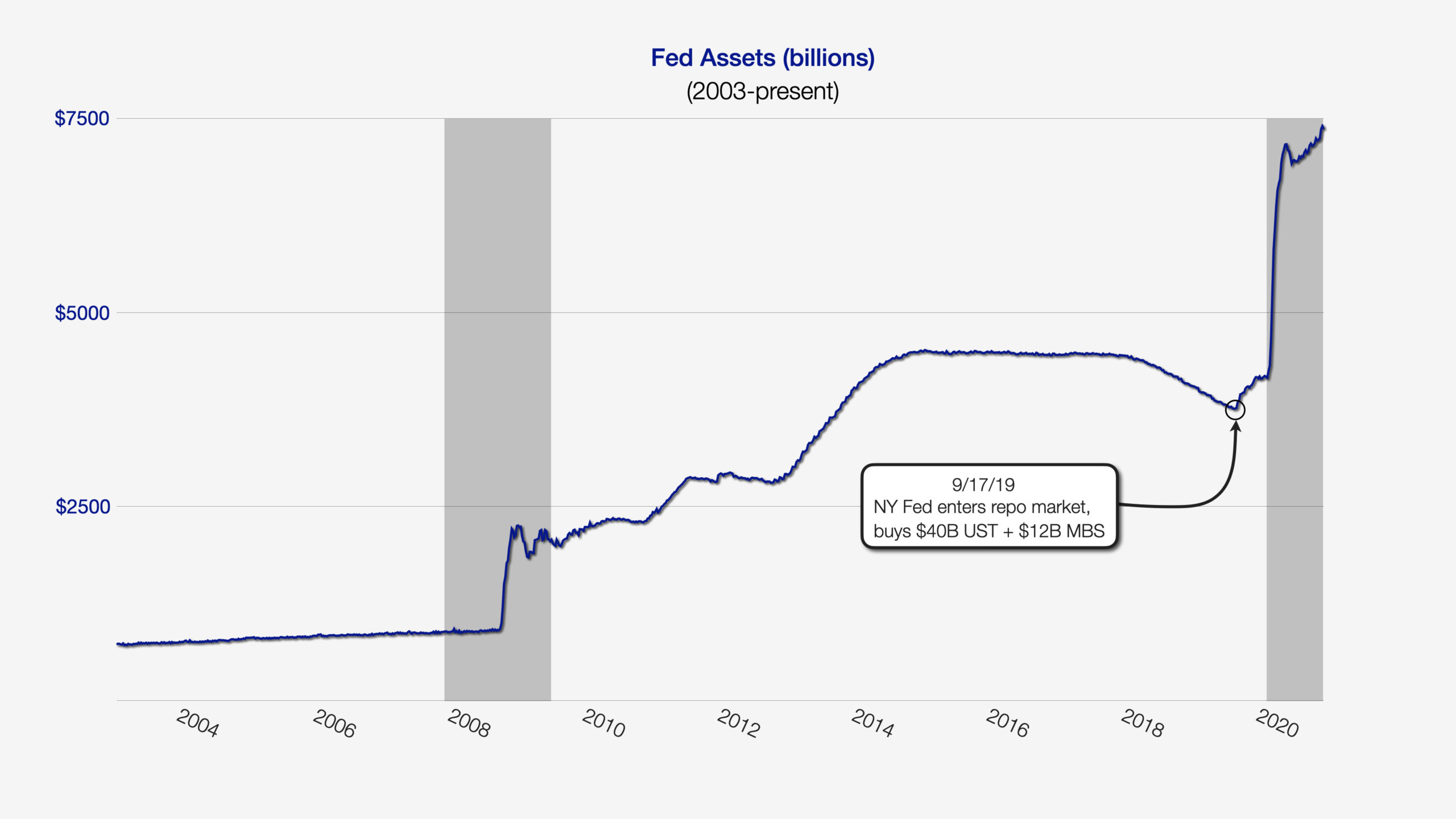

The New York Fed’s intervention in the repo market on September 17 marked a turning point for the Fed’s balance sheet, which had been steady or declining since 2015. At that point, the Fed began purchasing assets and thereby increasing the size of its balance sheet, just as it had done in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis. See chart, “Fed Assets (billions), 2003-present.” With any monetary crisis like the one in the repo market, one is well-advised to first investigate the U.S. bond market—the root of all U.S. money except for coins—for culprits. And there we find that foreigners had begun dumping U.S. Treasuries exactly when woes surfaced in the repo market, a process that continued into 2020.

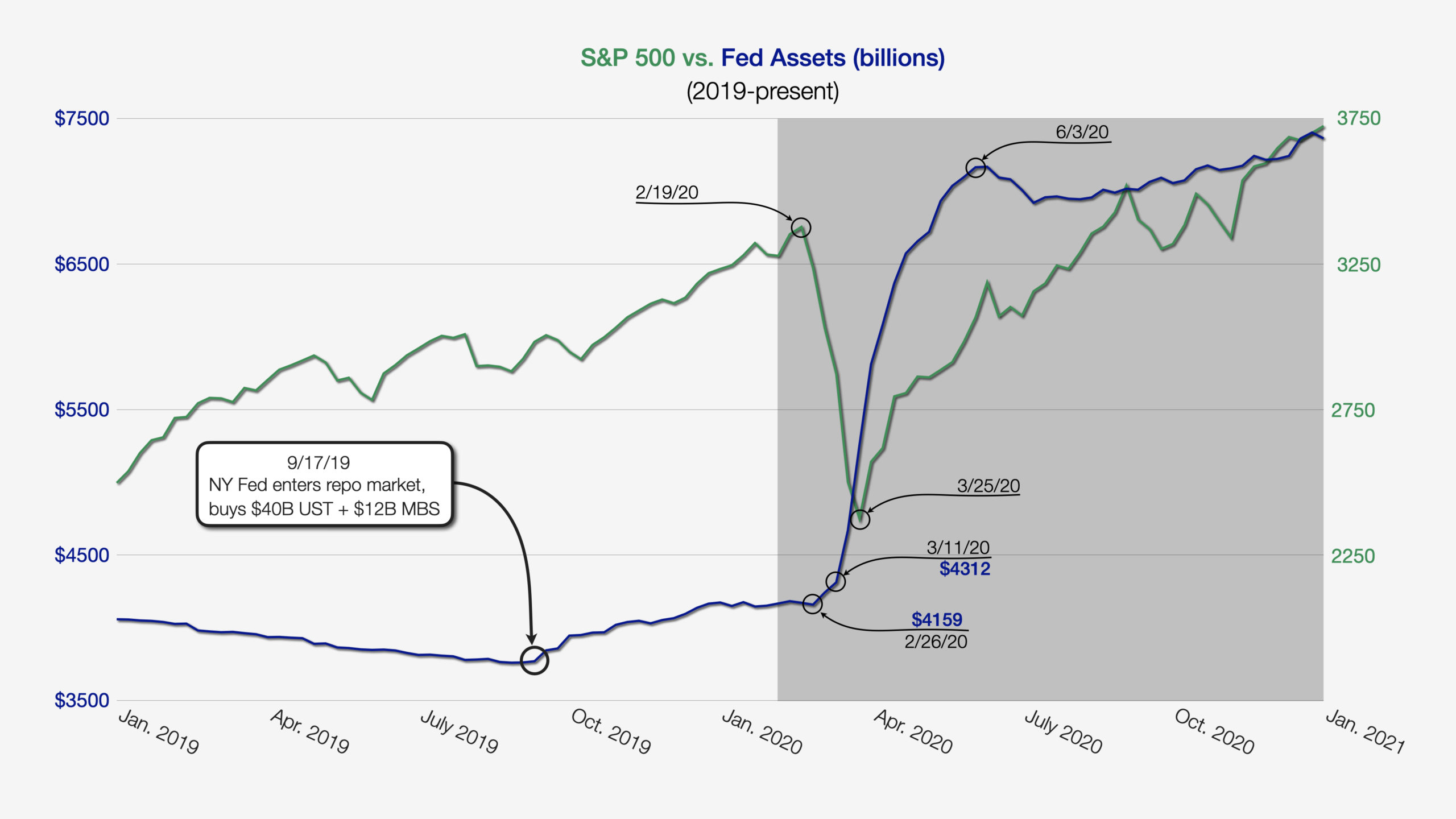

The Fed filled the gap left by foreign selling (a gap made even bigger by the ever-widening U.S. deficit, which is funded by… selling even more Treasuries) by creating new reserves and buying up U.S. government debt itself. For about five months, the Fed’s asset purchases were (in retrospect) modest, meaning they were limited to around $100 billion per month. What spurred the Fed to increase its efforts from low- to mid-gear was the stock market, which went into free fall starting on February 19, 2020. See chart, “S&P500 vs. Fed Assets, 2019-present.”

Over the two-week period from February 26 to March 11, the Fed ramped up its asset purchases by over $150 billion, but the stock market continued its free fall nevertheless.

On March 11, the WHO declared the budding coronavirus threat, small though it then was, a pandemic. When that happened, the Fed’s asset purchases immediately went into high gear. See “3/11/20” annotation on chart, “S&P500 vs. Fed Assets, 2019-present.”

To a casual observer, it might appear that the massive expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet began when the WHO declared the virus to be a worldwide pandemic on March 11. That is not the case, however. For one thing, as we’ve just seen, both “the next downturn” and the Fed’s expansion of its balance sheet began six months earlier, when the New York Fed intervened in the repo market.

For another, the expansion of the Fed’s balance sheet in accordance with BlackRock’s radical new plan to “get central bank money directly in the hands of public and private sector spenders” can be traced back to about February 1, 2020, well over a month before public officials hit the panic button over what was to become The Virus The Virus The Virus from March 11 forward.

Normally, that is, prior to the implementation of BlackRock’s “going direct” plan, when the Federal Reserve purchases assets, it buys them from commercial banks or from the U.S. government, both of which have accounts with the Fed. Whenever the Fed buys assets, regardless of whether or not under BlackRock’s plan, it creates brand-new reserves to do so.

Reserves function as money for commercial banks, which have accounts at the Fed, but do not function as money for ordinary people and non-bank businesses, who do not have accounts at the Fed. For ordinary people and non-bank businesses, money isn’t reserves, it’s bank money. (Cash is an altogether different animal for purposes of this discussion, which pertains to digital money only.) But the Fed cannot and does not create bank money. Commercial banks create bank money.

For commercial banks, reserves are asset-money, and bank money (i.e., ordinary checking and savings accounts) is liability-money.

So when the Fed buys assets from a commercial bank or the U.S. government, it creates new reserves and credits the bank’s or the government’s Fed account in the amount of those new reserves, and the seller transfers the asset to the Fed in exchange. The key takeaway here is that this simple two-party transaction structure results in an increase in reserves, but no net increase in bank money. The reason there is no change in bank money under the Fed’s normal asset purchase route is that there is no non-bank entity (and thus no bank money) involved in the transaction, which is simply a two-party transaction between the Fed and a Fed account holder (a commercial bank or the government), conducted entirely in reserves.

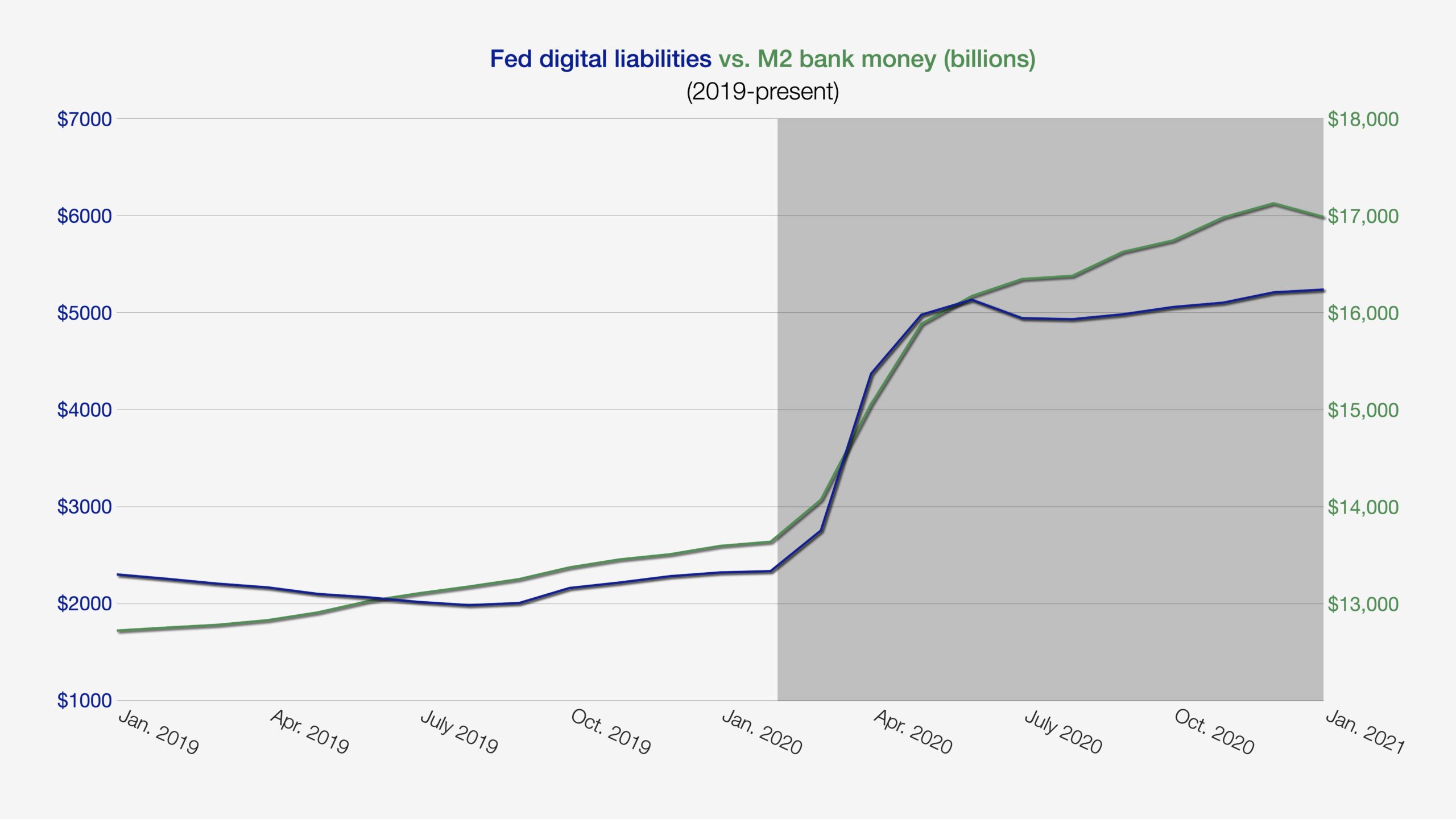

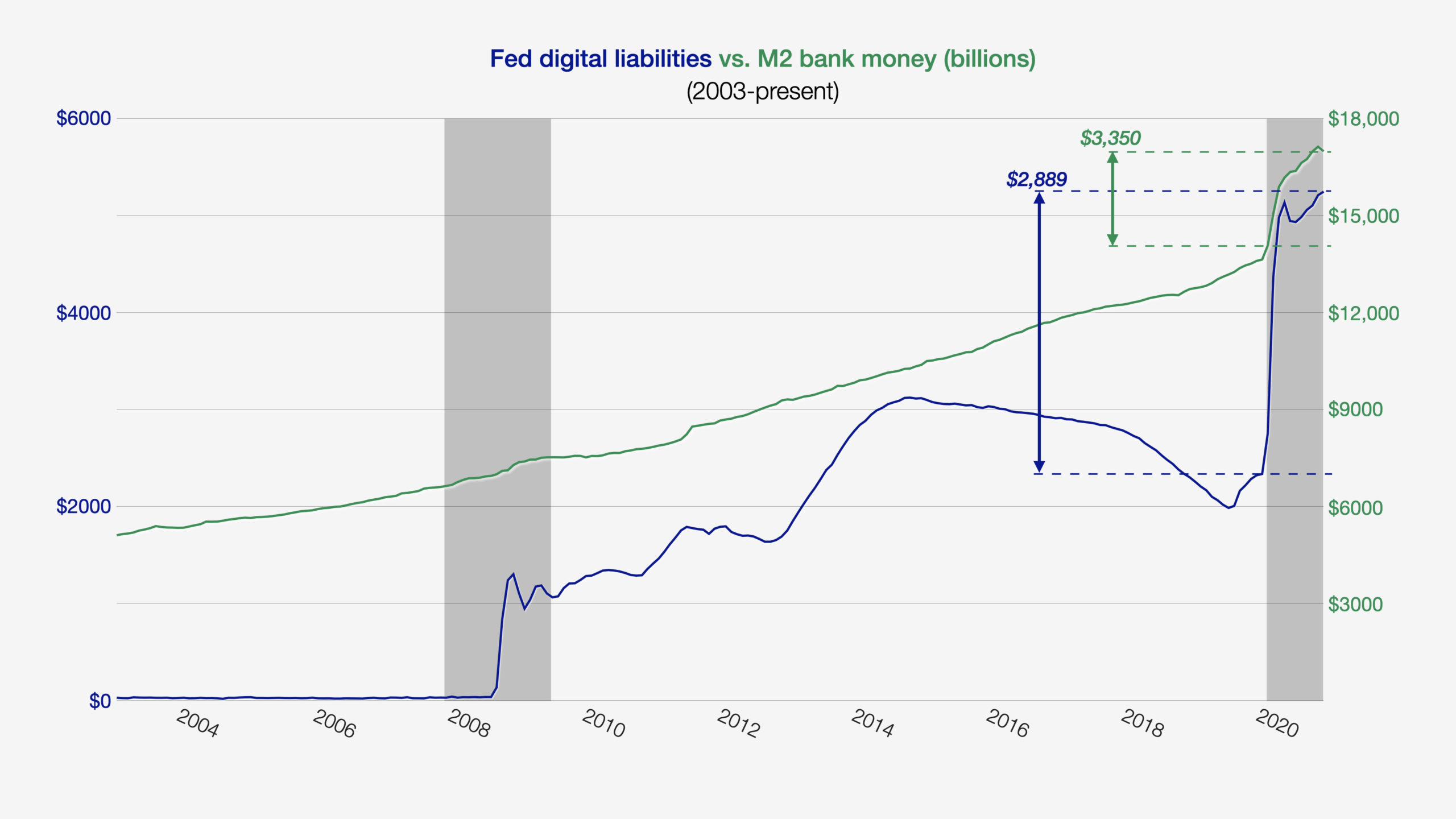

That traditional two-party asset purchase structure, however, gets abandoned by the Fed in February of 2020, however, replaced by a three-party asset purchase structure necessitated by BlackRock’s “going direct” plan of getting public money into private hands. From then on (throughout the recession period indicated by the Fed with a gray background on the graphs), what we see is the lockstep increase in both reserves and bank money. See chart below, “Fed digital liabilities vs. M2 bank money (billions), 2019-present.”

The reason for the lockstep increase in bank money reflects the presence of a third party, which doesn’t have a Fed account and uses bank money instead, in the new three-way asset purchase structure: the Federal Reserve (the asset buyer), a non-banking financial institution like a pension (the seller), and the seller’s commercial bank (which functions as the transaction intermediary).

Here is how that works. Instead of paying, say, $1000 of reserve money to the seller, the Fed pays the seller’s bank by crediting its Fed account with $1000 of new reserves; and the seller’s bank, in turn, credits the seller’s account with $1000 of brand new bank money. Thus, on the balance sheet of the seller’s bank, that $1000 of new bank money account became the liability that cancelled out the new $1000 in reserves sitting in the seller bank’s reserve account at the Fed. In this way, when the Fed purchased $3 trillion of assets in 2020, it forced the separate creation of $3 trillion in bank money.

The precise process is explained in detail by “Quantitative Easing Is the Biggest Sham Ever” (Best Evidence, Mafiacracy Now, Season 3, Episode 2), which revealed that the Federal Reserve structured its 2020 large-scale asset purchases (with newly created reserves) so as to force the creation of new money in the regular economy (with new bank-money created in mirror-image form to counterbalance the new reserves). This structure is designed to drive up high-risk financial assets like stock market equities, a fact that the Bank of England stated expressly in a 2014 publication.

This lockstep increase in new bank money in tandem with the Fed’s creation of new reserves to buy assets represents a massive and fundamental departure from the Fed’s QE program in the wake of the 2008 crisis. Back then, the Fed increased its digital liabilities (i.e., excluding cash) from basically zero to nearly $1.5 trillion in just a few months, and yet the supply of bank money hardly even registered a blip, as the chart below (“Fed digital liabilities vs. M2 bank money, 2003-present”) attests.

This is exactly what BlackRock had advocated in its “going direct” plan: “the central bank finding ways to get central bank money directly in the hands of public and private sector spenders.” The private sector spenders, of course, are the non-bank financial institutions that sold the Fed assets, mostly U.S. Treasuries. As explained in “Quantitative Easing Is the Biggest Sham Ever,” non-bank financial institutions like pension funds are fully motivated, in order to generate higher rates of returns to keep up with fund withdrawals, to replace lower yielding assets like U.S. Treasuries with higher-yielding assets like stock market equities.

The mechanics of the Fed’s 2020 balance sheet expansion is an important confirmation of the Federal Reserve’s dominion over commercial banks, which despite conventions (e.g., reserve creation following rather than leading bank money creation) and numbers (e.g., reserve money being but a fraction of M2, a reliable proxy for bank money) remain the legally inferior party.

The massive balance sheet expansion that occurred during 2020 was thus unprecedented not only for its size (over $3 trillion of new reserves) but also in its mirror image creation of new bank money (as shown in the graph above, “Fed digital liabilities vs. M2 bank money, 2019-present”). The mirror image creation of public and private money via the structure of the Fed’s asset purchases was scripted by BlackRock some four months before any virus story emerged from Wuhan.

In this we can observe the 24/7 Virus coverage as a collateral script—a literal sequel—that functions to rationalize the implementation of BlackRock’s original monetary script, which indeed expressly called for “the next downtown.”

Neither the Fed nor the big banks that own the Fed have been particularly subtle about sharing their insights on what the Virus might do next, as if it were a character on a TV show. The financial website zerohedge.com can’t seem to go an entire day without offering up Goldman Sachs or Bank of America’s latest thoughts about what the Virus has in store for the economy. The authors of these scientific tracts and prognostications don’t have any qualifications in epidemiology or infectious diseases because that’s not what the Virus is about, and scientific credentials are unnecessary.

What it’s about is the Fed setting public policy. This is why President Neel Kashkari of the privately owned Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank spoke before an audience of 5 million people on Face the Nation in April 2020: to warn them to expect 18 months of lockdowns because “the path of the virus” included “various phases of rolling flare-ups.” See “Presenting The Federal Reserve Script for Totalitarianism” (BestEvidence, Mafiacracy Now, Season 2, Episode 3).

C. Significance of the Fed’s 2020 Balance Sheet Expansion

The Fed’s encroachment during 2020 into the currency-issuing role traditionally held by commercial banks in the U.S. has been both massive and unprecedented. This development has not garnered any news coverage because quantitative easing—despite its major splash onto the financial scene 12 years ago—is still not well understood. In this regard, while the Fed’s $3 trillion balance sheet expansion is widely known, the fact that this expansion in turn forced the additional creation of $3 trillion by commercial banks is not known at all. Stated differently, while it’s widely known that the Fed created $2.9 trillion in new reserves (which cannot be used by non-banks in the regular economy) out of thin air in 2020, sending its overall balance sheet north of $7 trillion, few people understand that this action forced commercial banks to create $3.3 trillion of brand new bank money (which certainly can be used by non-banks in the regular economy). See above graph, “Fed digital liabilities vs. M2 (billions), 2003-present.”

This reflects a breathtaking exercise of monetary power by the Federal Reserve when one considers that the Fed’s actions during 2020 accounted for some 86% ($2.889T of $3.350T, see graph annotations) of new bank money. Commercial banks, which are the exclusive issuers of bank money, accounted for only 14% of its new issuance last year.

Why does any of this matter? It matters because it marks the Fed’s major move in its eventual takeover of money-creating functionality from commercial banks, which when it comes to central bank digital currencies will be 100%. And this, in turn, represents the first step in the global centralization of monetary control in the hands of some unelected global entity without the first scintilla of any transparency or accountability.

D. The Fed’s Execution of BlackRock’s “Going Direct” Plan

Enriched Billionaires While Main Street Struggled

The Fed’s execution of BlackRock’s plan inured to the enormous benefit of financial asset holders, whose low-yield U.S. Treasuries (or sketchy mortgage-backed securities) they were able to fob off onto the Fed’s balance sheet in exchange for cash (via a commercial bank intermediary that “converted” reserves into bank money). Those financial asset holders were then able to turn around and plow their cash into high-yield assets like the stock market. Indeed that’s a central purpose of QE, as demonstrated in “Quantitative Easing Is the Biggest Sham Ever.”

The Fed’s implementation of BlackRock’s plan to “go direct”—directly from the new reserves created by the Fed into new bank money created by commercial banks in the accounts of financial asset holders for them to invest—was a success from very early on in the pandemic, at least when contrasted with the relief afforded to Main Street: “Between March 18 and April 10, as the U.S. employment rate approached 15 percent, the combined wealth of America’s billionaires increased by $282 billion – nearly a 10 percent increase.”

And the April 10 figure of $282 billion, recall, is the wealth increase over the course of less than a single month, and just for billionaires at that.8 As we’ve just seen, that wealth increase was enabled by the Fed’s execution of BlackRock’s “going direct” plan, which makes it an interesting basis for comparison against the Fed’s supposed efforts to help Main Street.

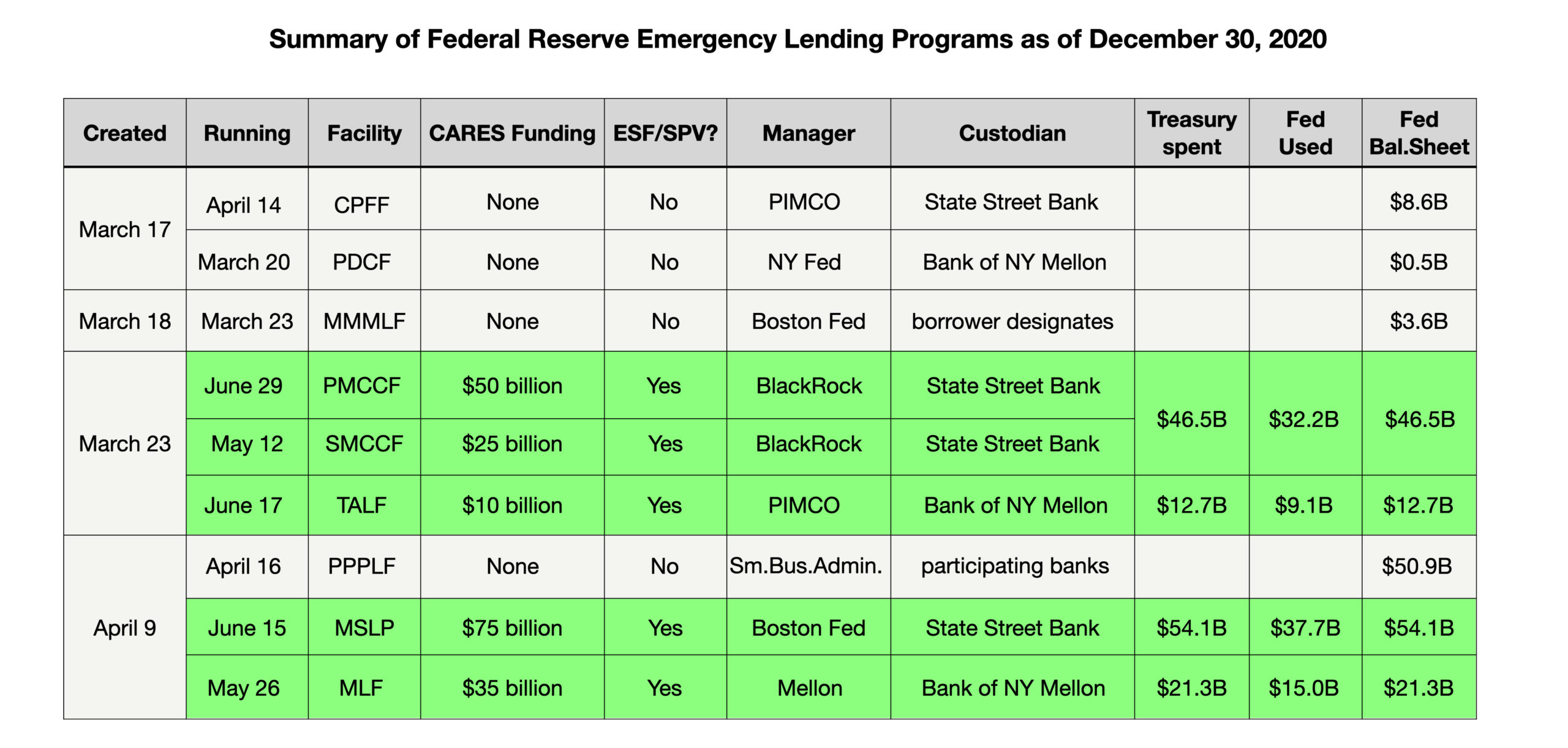

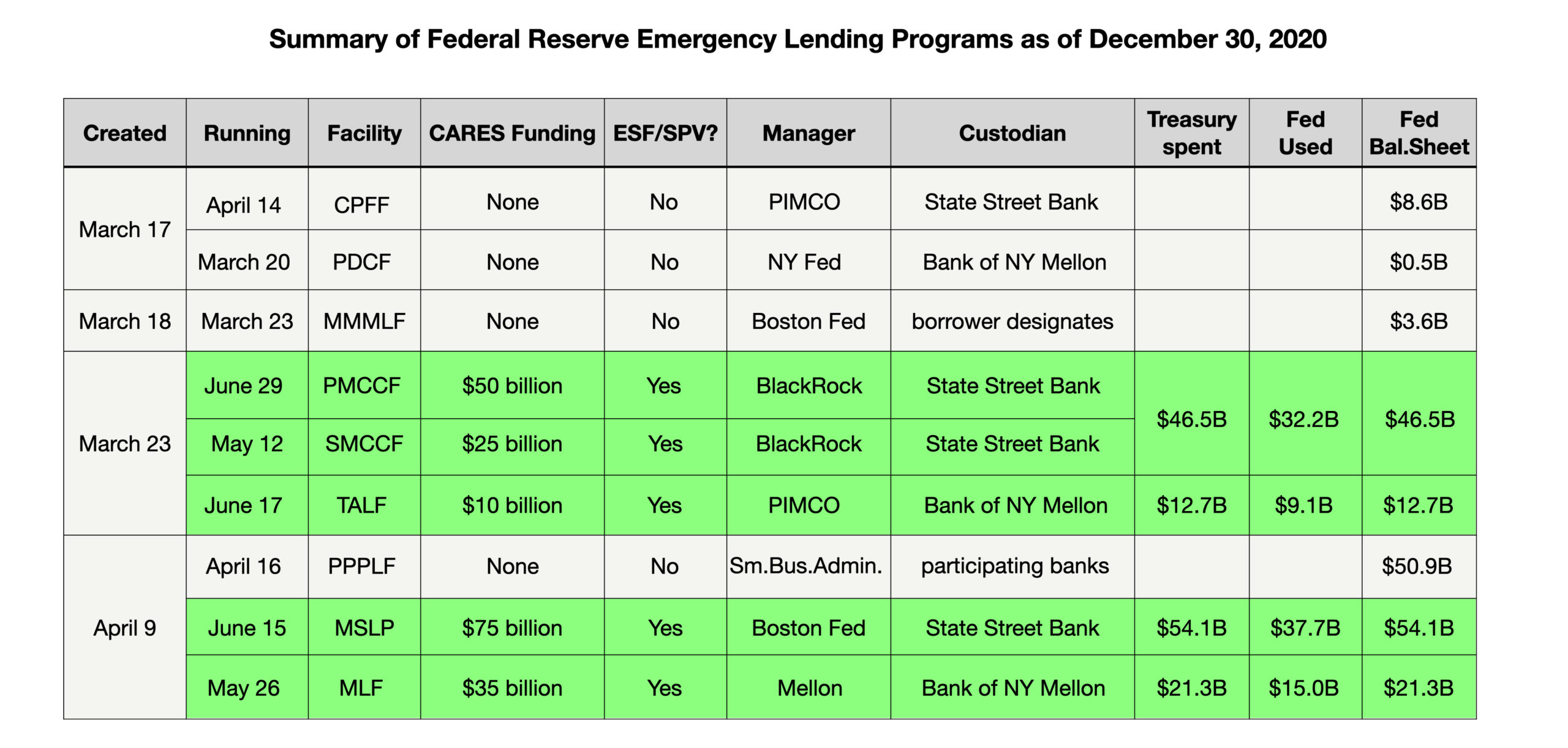

The key date here is April 10, 2020. By that time, the Fed had created six lending programs for Main Street on two different dates, March 23, 2020 and April 9, 2020.9 At first blush, then, it might appear that the Fed, while “unavoidably” helping billionaires, had lent at least some money to Main Street via these six programs. But alas, this is not the case, because none of the Fed’s Main Street programs was even up and running by April 10.

In fact, the first operational Main Street program was the Paycheck Protection Program Liquidity Facility (PPPLF), which wasn’t operational until April 16. The next Main Street Fed lending program to become operational was the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF), which wasn’t up and running until May 12, 2020, as the above table of programs illustrates; green highlighting indicates those programs that required a special purpose vehicle (SPV) in the form of the Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF).

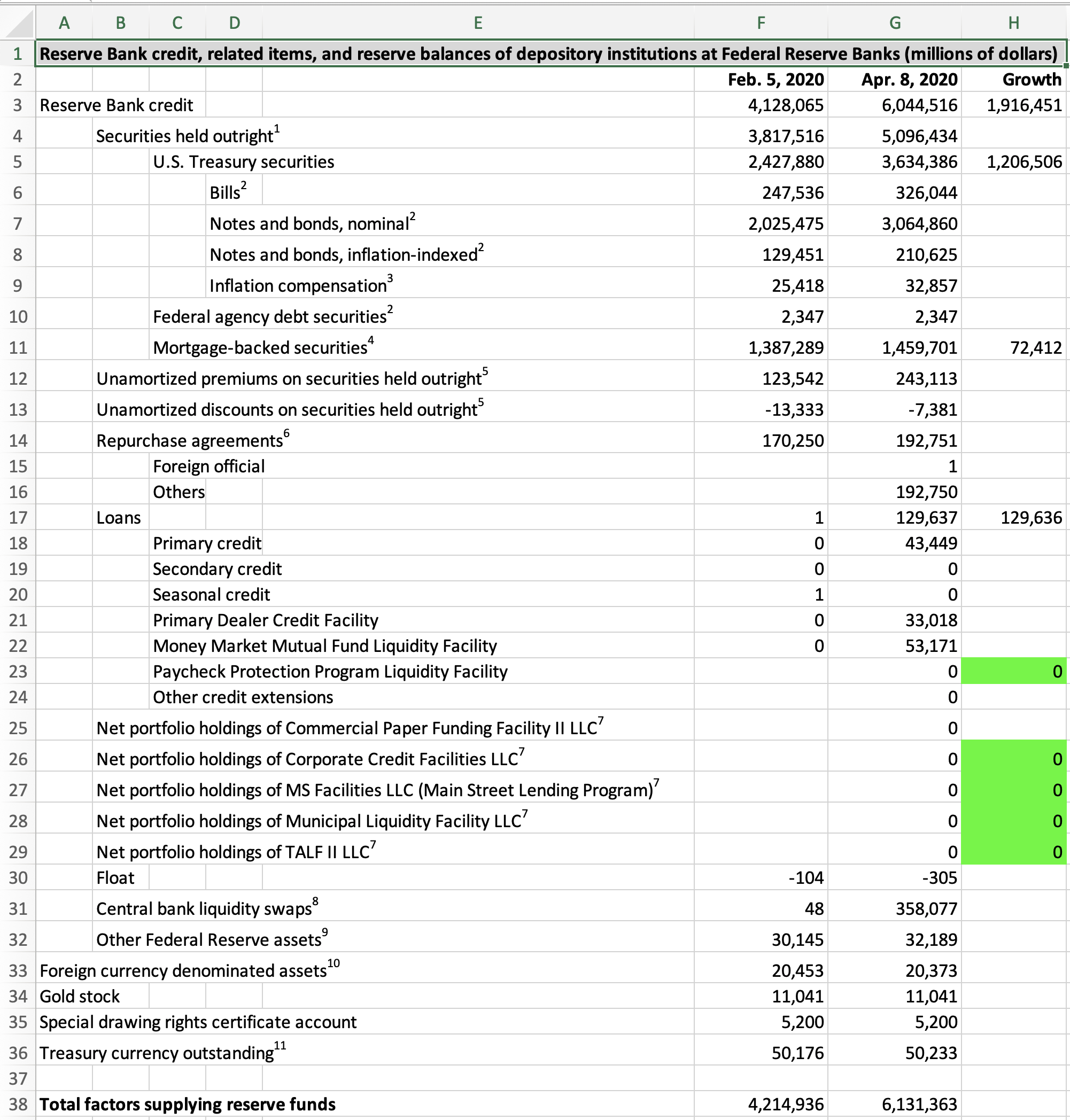

By April 10, 2020, then, the Federal Reserve had bestowed exactly zero money on Main Street despite a host of programs supposedly set up to do exactly that. By that very same date, by contrast, the Fed had purchased more than $1.2 trillion of U.S. Treasuries in accordance with BlackRock’s plan and had extended more than $130 billion to Wall Street programs, as the following comparison of the Fed’s balance sheet on February 5 and April 12, 2020 reveals.

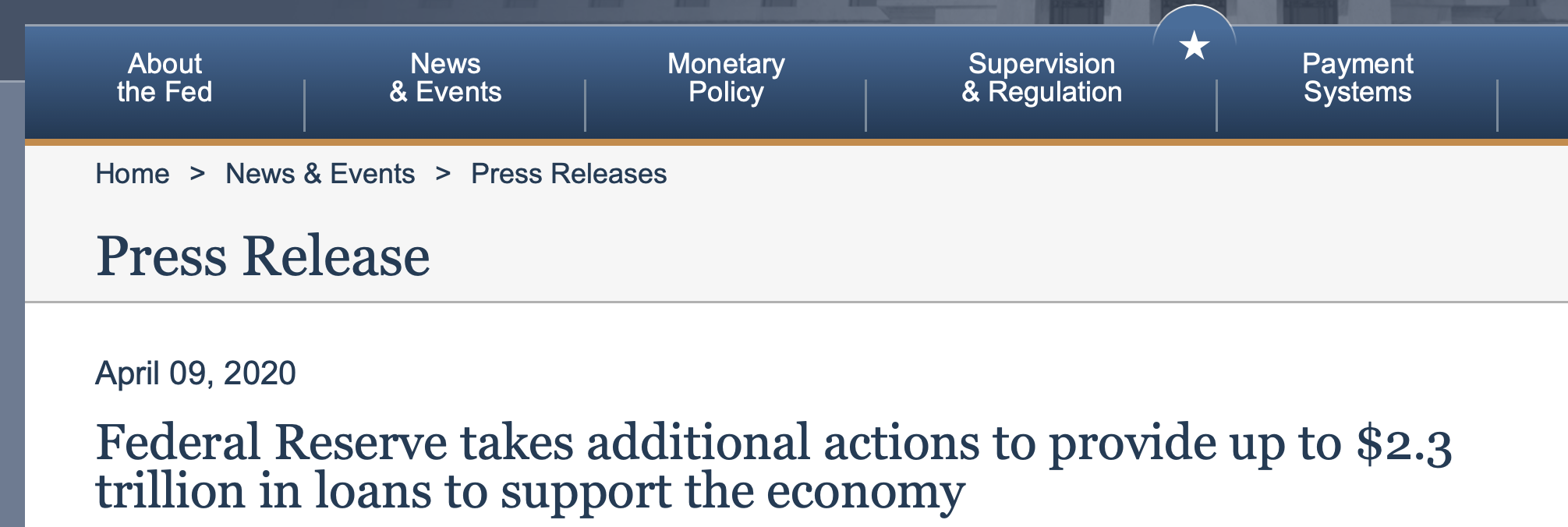

As always, the Fed’s only real interest in Main Street consisted of PR efforts, which during the pandemic wildly exaggerated the reality of the Fed’s efforts on Main Street’s behalf. And thus it was one day before April 10: Despite having failed to lend the first actual penny to anyone under the Fed’s so-called Main Street programs, the Fed in its April 9 press release crowed about a massive (and imaginary) $2.3 trillion funding of its Main Street programs to “assist households and employers of all sizes and bolster the ability of state and local governments to deliver critical services during the coronavirus pandemic.”

On the ground, of course, Main Street had been shut down for nearly a month, putatively in response to the novel coronavirus. Thus, the media’s 24/7 Virus Virus Virus production not only deflected attention away from the real source of Main Street’s pain, which was unemployment brought on by lockdowns; it also provided cover for the Fed’s radical and massive balance sheet expansion that was turning billionaire financial asset holders into trillionaires. That was in fact BlackRock’s plan all along, and it worked.

E. Real Help for Ordinary Americans Didn’t Come from the Federal Reserve

While the Fed was busy ginning up wildly misleading press releases utterly belied by painful reality, real help for ordinary Americans came from elsewhere. What actually buffered Main Street from the full brunt of the lockdowns wasn’t the Fed’s self-aggrandizing and empty press releases, it was actual money in the form of loans (possibly forgivable) from the Small Business Administration’s (SBA’s) Paycheck Protection Program (PPP).

The Federal Reserve’s lending facility bearing the same name is just another cynical attempt by the Fed to seek favorable publicity where precious little is due, as the following comparison of the two PPP programs shows.

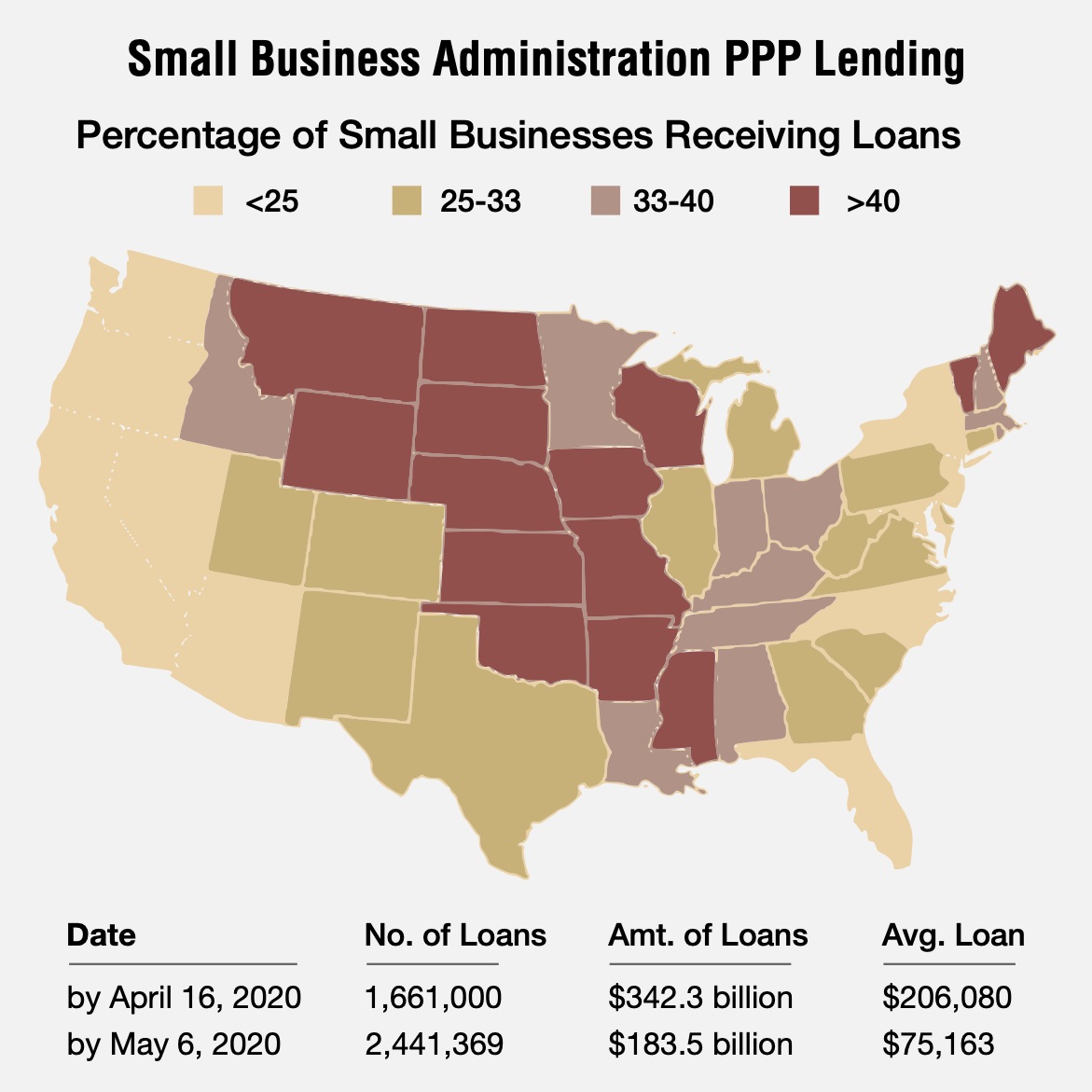

As we’ve just seen, by April 10, 2020, the Fed’s PPP facility wasn’t even operational yet. That didn’t occur until April 16. By that date, the SBA had already extended $342 billion in relief to Americans by providing 1.7 million loans to small- and medium-sized businesses at an average amount of $206,000 per loan.

Despite the fact that the Fed had lent out no money by April 16, its report to Congress that very day was eager not only to latch onto the SBA’s coattails, but to make it appear that the Fed’s PPP lending facility was enabling loans under the SBA’s PPP facility—a clear impossibility in view of the timing. Here is what the Federal Reserve told Congress on April 16, 2020:

The PPPLF offers a source of liquidity to the financial institution lenders who lend to small businesses through the Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Paycheck Protection Program (PPP).

Nowhere in the Federal Reserve’s report to Congress does it describe the Fed’s PPPLF as supplemental to or parallel with the SBA’s program by the same name. Nor does the Fed even acknowledge the massive $340 billion effort by the SBA—an effort that occurred with no help from the Fed at all. Instead, the Fed casts its PPP program as if it’s an inherent part of the SBA, a plain impossibility.

Even when the Fed did get its PPPLF up and running, its lending activities were dwarfed by those of the SBA’s PPP program (which in turn were dwarfed, sadly, by the Fed’s financial-asset-pumping purchases). By May 6, 2020, when the SBA had lent out some $525 billion to businesses, the Fed’s PPPLF stood at just $29 billion, a 20-to-1 ratio.

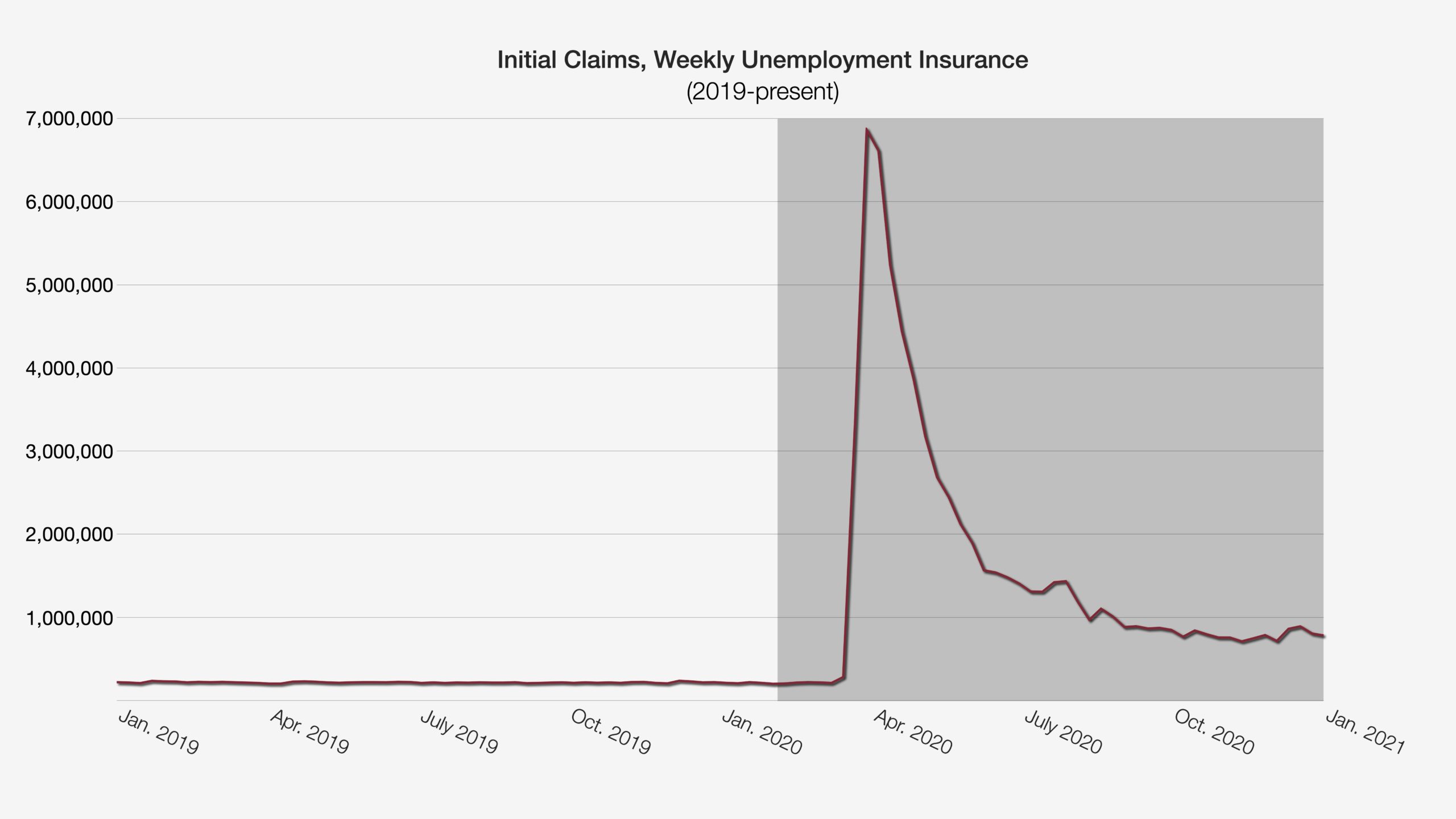

These dates are centered on the brunt of the crisis, too, as the following chart of Initial Unemployment Insurance Claims makes clear:

F. So, What Were the Fed’s Emergency

Lending Programs Really All About?

The media’s coverage of pandemic programs and responses by both the Federal Reserve and the U.S. government was thoroughly incompetent, vastly over-emphasizing the Fed’s Main Street and other emergency lending programs while giving short shrift to (1) the Fed’s $3 trillion reserves creation efforts ($6 trillion if you count bank money, for reasons explained above) and (2) the SBA’s Herculean accomplishment of marshaling 5.2 million loans at an average value of $100,000 per loan for a total of $525 million in relief.

Nevertheless, it is precisely because the Fed’s emergency lending programs drew so much digital ink that we provide a short compendium for easy reference. A good starting point for this exercise is the emergency lending summary shown above and reproduced here.

1. Overview of How the Fed’s Emergency

Lending Programs Worked

As discussed above, the Fed’s “Main Street” programs are those created (left column) on March 23 and April 9, 2020. At the end of 2020, these programs accounted for $185.5 billion on the Fed’s balance sheet (rightmost column)—on the asset side of the balance sheet since the loans were all collateralized. Note that the Custodian is always a commercial bank (even when designated by the borrower). The reason for this is that the Fed can only create new reserves, whereas the ultimate program borrowers are non-bank businesses that transact their business in bank money and don’t have an account at the Fed. Thus, the Federal Reserve needs an intermediary commercial bank to “convert” reserves from the Fed into bank money that’s lent out to program recipients.

In reality, that “conversion” process is really just the commercial bank booking new reserves (of which it is custodian) as an asset and creating new bank money for lending and booking that as a liability, thereby balancing its ledger. In any case, the Fed cannot create bank money and needs a commercial bank to perform that function for it.10

Another column worth noting is “ESF/SPV?” All but one of the Main Street lending facilities are ticked “Yes.” ESF is short for “Exchange Stabilization Fund.” When Congress passed the CARES Act on March 27, it allocated $500 billion to the ESF, of which $454 billion was to be used for the Fed’s emergency lending programs above.

The media frequently cited the Fed’s intention to leverage the ESF’s “investment” with the Fed at a 10-to-1 ratio, which just happens to match the reserve ratio before it was scotched. This fueled the popular notion that the Fed needed money from the Treasury in order to lend through these programs, which is utterly false. The Federal Reserve is a bank of issue; it creates all reserves out of thin air, just as commercial banks create bank money out of thin air. (See BestEvidence, “Mommy, Where Does Money Come From?”.) The Fed didn’t need a penny from the Treasury or anyone else, contrary to the myth promoted by the media.

The more likely explanation for the presence of the ESF relates to its historical role in skirting or altogether evading the law, largely enabled by its location within the privately owned New York Federal Reserve. In the mid-1990s, for instance, Congress refused to pass legislation bailing out the Mexican peso, so the Clinton Administration simply set up a $20 billion lending package and ran it from the ESF in 1995. Another instance: When money market mutual funds experienced heavy redemptions in September 2008, the Treasury unilaterally guaranteed money market mutual funds with $50 billion from the ESF. This sufficed to end redemptions despite the fact that money market mutual funds held about $3.5 trillion in assets then, whereas the ESF held just $50 billion, which should have rendered (but evidently did not) the ESF’s guarantee a laughingstock.

The presence of the ESF in the Fed’s emergency lending facilities is also very likely a move by the Fed to block any efforts at transparency. As Rob Kirby, who’s studied the ESF for many years, puts it: “It was operated above all laws and was subject to no laws. So this was an entity that was created with the almighty hammer, bigger money than any entity had ever had at its disposal prior, and it had free hand to do whatever it wanted.”

In any case, the Federal Reserve implemented a host of liquidity facilities—most but not all operated by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York—on the heels of the pandemic and associated lockdowns. As it had done during the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed established several facilities under section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, which empowers the Fed (with the approval of the U.S. Treasury) to establish, in “unusual and exigent circumstances,” broad-based lending programs.

And just as it did during the 2008 financial crisis, the Fed did not hesitate to take actions that went beyond the bright-line legal boundaries set by section 13(3), for example by purchasing assets (instead of borrowing them). This is the true reason the Fed resorts to special purpose vehicles (SPVs), a kind of legal cutout or strawman that (in the Fed’s mind) steps into the Fed’s shoes to do things that are legally off-limits to the Federal Reserve itself.

For example, to get around the legal prohibition against the Fed purchasing assets, which limits the Fed to making loans, the Fed during the 2008 crisis set up numerous SPVs. The Fed then lent money to these SPVs, which turned around and purchased the assets, which were used as collateral by the SPVs against their so-called loans.

After the financial crisis, congress modified the law (via Dodd-Frank) to further limit the range of activities available to the Fed under section 13(3). Throughout the crisis, for example, the Fed repeatedly assisted particular institutions in blatant displays of favoritism. Dodd-Frank prohibited that practice by the Fed, prohibiting it (supposedly) from targeting specific entities. Under this reform, the Fed is only allowed to undertake broad-based loans.

During the pandemic, however, the Fed dealt with any and all limitations on its legal authority under section 13(3) the same way it did during the 2008 crisis, namely, by setting up SPVs to undertake acts forbidden to the Federal Reserve itself. The Fed then inserted the ESF for good measure, like wearing suspenders with a belt.

Detailed information from reports on each program–including, where applicable, transaction-level details logged in spreadsheets–can be found on the Federal Reserve’s website.

2. Thumbnail Summaries of the Fed’s

Emergency Lending Programs

By way of that general background, provided here is a short summary of the Fed’s specific emergency lending facilities during the pandemic. Figures provided are as of year-end 2020.

a. Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF)

According to the New York Fed, the commercial paper market experienced serious problems during the week of March 20, 2020. Of particular concern was the alleged inability of certain firms to issue paper for any term longer than one week. The Fed accordingly set up the CPFF in order to ease payments of auto loans, inventories, and payrolls.

The Fed’s credibility with CPFF is not good. This is the program’s second iteration, the first being in the wake of the global financial crisis of 2008. The Fed refused to provide any information relating to which institutions received funding under the CPFF. In 2010, however, a partial audit by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) forced the disclosure of recipients. The results were not flattering for the Fed. Contrary to the story it had provided to Congress relative to the Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP)—namely, that Wall Street needed to be bailed out in order to bail out Main Street via the commercial paper market—it turned out that of $800 billion provided to institutions under the CPFF, not even $1 went to any Main Street businesses. See the BestEvidence video “Ben Bernanke’s Sovereign Deception” (timestamp 8:05) for the list of CPFF recipients, including UBS (Switzerland), Dexia (Belgium), Barclays (UK), and others.

Thumbnail Summary of CPFF

- Authorized up to: No CARES limit

- Current amount: $9 billion

- Treasury equity: $0

- SPV? No

- Transaction detail? No

b. Municipal Liquidity Facility (MLF)

Created pursuant to the CARES Act and under section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, the Fed’s MLF facility is intended to help states, counties (with a population of over 500,000), and cities (250,000+) deal with cash flow pressures. Under this program, the Fed lends to the SPV, which in turn purchases (via Bank of New York Mellon, which books the SPV’s reserves as an asset and creates a matching deposit account liability in the name of the municipality) notes from municipalities.

Thumbnail Summary of MLF

- Authorized up to: $500 billion

- Current amount: $21.3 billion disbursed by Treasury

- Treasury equity: $35 billion authorized

- Treas. eq. used: $15.0 used by Fed

- Outstanding 12/30: $6.4 billion

- SPV? Yes

- Transaction detail? Yes

c. Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF)

Created under section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, the PDCF is, like CPFF, a retread from the 2008 financial crisis. The chief difference is that the current PDCF provides for dealer loans of up to 90 days, whereas the first version of PDCF provided only for overnight loans.

Thumbnail Summary of PDCF

- Authorized up to: No CARES limit

- Current amount: $485 million

- Treasury equity: $0

- SPV? No

- Transaction detail? No

d. Corporate Credit Facility (PMCCF and SMCCF)

Created pursuant to the CARES Act and under section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, both the Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility (PMCCF) and Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF) are intended to provide access to credit so that large companies (PMCCF) and smaller companies (SMCCF) can maintain business operations and capacity. Under the PMCCF, the Fed lends to the SPV, which in turn purchases (via State Street Bank, which books the SPV’s reserves from the Fed as an asset and creates a matching deposit account liability in the name of the company) bonds directly from eligible companies. Under the SMCCF, the Fed makes three classes of bond purchases from the secondary market: individual corporate bonds, exchange traded funds (ETFs), and broad market index bonds.

Thumbnail Summary of PMCCF and SMCCF

- Authorized up to: $750 billion

- Current amount: $46.5 billion disbursed by Treasury

- Treasury equity: $75 billion authorized

- Treas. eq. used: $32.2 billion used by Fed

- Outstanding 12/30: $14.1 billion (of $75 billion)

- SPV? Yes

- Transaction detail? Yes (SMCCF) No (PMCCF)

This pair of facilities, but especially the SMCCF, warrants further study in view of what’s known about BlackRock’s role as program manager (see previous table). In short, BlackRock was using its position of legal authority to buy ETFs owned by BlackRock itself. This presented BlackRock with the opportunity to self-deal, which it exercised liberally: “Between May 14 and May 20, about $1.58 billion in ETFs were bought through the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF), of which $746 million or about 47% came from BlackRock ETFs.”

e. Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility (TALF)

Created pursuant to the CARES Act and under section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, TALF enables the issuance of asset-backed securities backed by student loans, auto loans, credit card loans, loans guaranteed by the Small Business Administration (SBA), leveraged loans, commercial mortgages, and certain other assets. While this program sounds like it might be directed toward ordinary businesses, TALF funding is available only to “maintain an account relationship with a TALF Agent.” The list of TALF Agents is 15 securities firms, most of which are the New York Fed’s primary dealers. For an egregious abuse of this program, see the August 31, 2020 timeline entry.

Thumbnail Summary of TALF

- Authorized up to: $100 billion

- Current amount: $12.7 billion disbursed by Treasury

- Treasury equity: $10 billion authorized

- Treas. eq. used: $9.1 billion used by Fed

- Outstanding 12/30: $4.1 billion (of $10 billion)

- SPV? Yes

- Transaction detail? Yes

f. Paycheck Protection Program (PPP).

Created pursuant to the CARES Act and under section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, the PPP is the most interesting in the seeming bifurcation of support provided by the Federal Reserve on the one hand and the U.S. government on the other hand. Under the PPP, the Fed claims to be “supplying liquidity to participating financial institutions through term financing backed by PPP loans to small businesses.” According to an April 16, 2020 report on the program by the Fed to Congress, the Fed set up a lending facility (the PPPLF), which “offers a source of liquidity to the financial institution lenders who lend to small businesses through the Small Business Administration’s (SBA) Paycheck Protection Program (PPP).”

While the Fed’s balance sheet (as of December 30, 2020) contains a PPP entry in the amount of $54 billion, the Small Business Administration website indicates that participation in the program has exceeded $500 billion, and that participation in the program is extremely widespread, as indicated by the color-coded participation levels in the chart shown above.

Thumbnail Summary of PPP

- Authorized up to: $349 billion, increased to $659 billion on April 27

- Current amount: $54 billion

- Treasury equity: None

- SPV? No

- Transaction detail? Yes

g. Main Street Lending Program (MSLP)

Created pursuant to the CARES Act and under section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, the Main Street Lending Program (terminated on January 8, 2021) was intended to support lending for small- and mid-sized businesses that were in sound financial condition before the pandemic. (The program’s term sheet, however, indicates that businesses with up to 10,000 employees or $2.5 billion in annual revenue were eligible for loans ranging from $1 million to $25 million.) Under this program, the Boston Fed established the Main Street SPV, which interfaced with some 640 eligible lenders in all 12 Fed districts to provide loans to businesses. Based on transaction-level detail provided by the Boston Fed, the earliest participation in the Main Street Lending Program appears to be July 1, 2020, when Cherry Tree Dental LLC of Madison, Wisconsin got a $12.3 million five-year loan from Starion Bank of Bismarck, ND.

Thumbnail Summary of MSLP

- Authorized up to: $600 billion

- Current amount: $54.1 billion disbursed by Treasury

- Treasury equity: $75 billion authorized

- Treas. eq. used: $37.7 billion used by Fed

- Outstanding 12/30: $16.4 billion

- SPV? Yes

- Transaction detail? Yes

h. Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (MMLF)

Created under section 13(3) of the Federal Reserve Act, the MMLF is nominally intended by the Fed to “broaden its program of support for the flow of credit to households and businesses.” The actual meaning of the phrase “broadening support for credit flow” is reflected in the program’s eligible participants, which are limited to banks, bank holding companies and U.S. branches and agencies of foreign banks. Under the MMLF, the Boston Fed “will make loans available to eligible financial institutions secured by high-quality assets purchased by the financial institution from money market mutual funds.” According to the Fed, the purpose of these loans is to “assist money market funds in meeting demands for redemptions by households and other investors, enhancing overall market functioning and credit provision to the broader economy.”

Thumbnail Summary of MMLF

- Authorized up to: No limit

- Current amount: $4 billion

- Treasury equity: $10 billion

- SPV? Yes

- Transaction detail? No

3. Who Was Really Served by the

Fed’s Emergency Lending Programs?

BlackRock was selected as the manager of both the Primary and Secondary Corporate Credit Facilities. Other financial institutions such as Pimco were tapped to manage other emergency lending programs as well. All of these firms are private and are motivated first and foremost to seek profits on behalf of their shareholders—not to protect the interests of the U.S. despite the U.S. Treasury’s investment of over $100 billion in programs run by these firms.

The issue of whose interests exactly these private firms were serving was raised by congress and put to Fed Chairman Jerome Powell and U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin in a Senate Report dated May 18, 2020:

The Fed has hired the firm BlackRock to serve as an investment manager for this facility. How is the Fed ensuring BlackRock is acting in the best interest of the Fed and the public?

In response to the Senate’s question about making sure BlackRock was acting “in the best interest of the Fed and the public,” Mnuchin and Powell candidly confirmed that BlackRock was not acting to protect the public at all, but instead acted for the sole benefit of the New York Fed—a private bank:

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York (“FRBNY”) is the sole managing member of the CCF. Pursuant to the [investment management agreement], BlackRock acts as a fiduciary to the CCF in performing investment management services.

In this example, we can see how private interests have seized control of governmental powers—including that of money creation—to benefit themselves without any meaningful limitations at all. In short, it is these private interests that are using sovereign powers belonging to we-the-people to literally pick winners and losers. This is the logical extension of BlackRock’s going direct plan and indeed was codified by BlackRock in a later policy plan that it released in June, as discussed in the next section.

G. The Historical Significance of the Fed’s

Actions in “Going Direct”

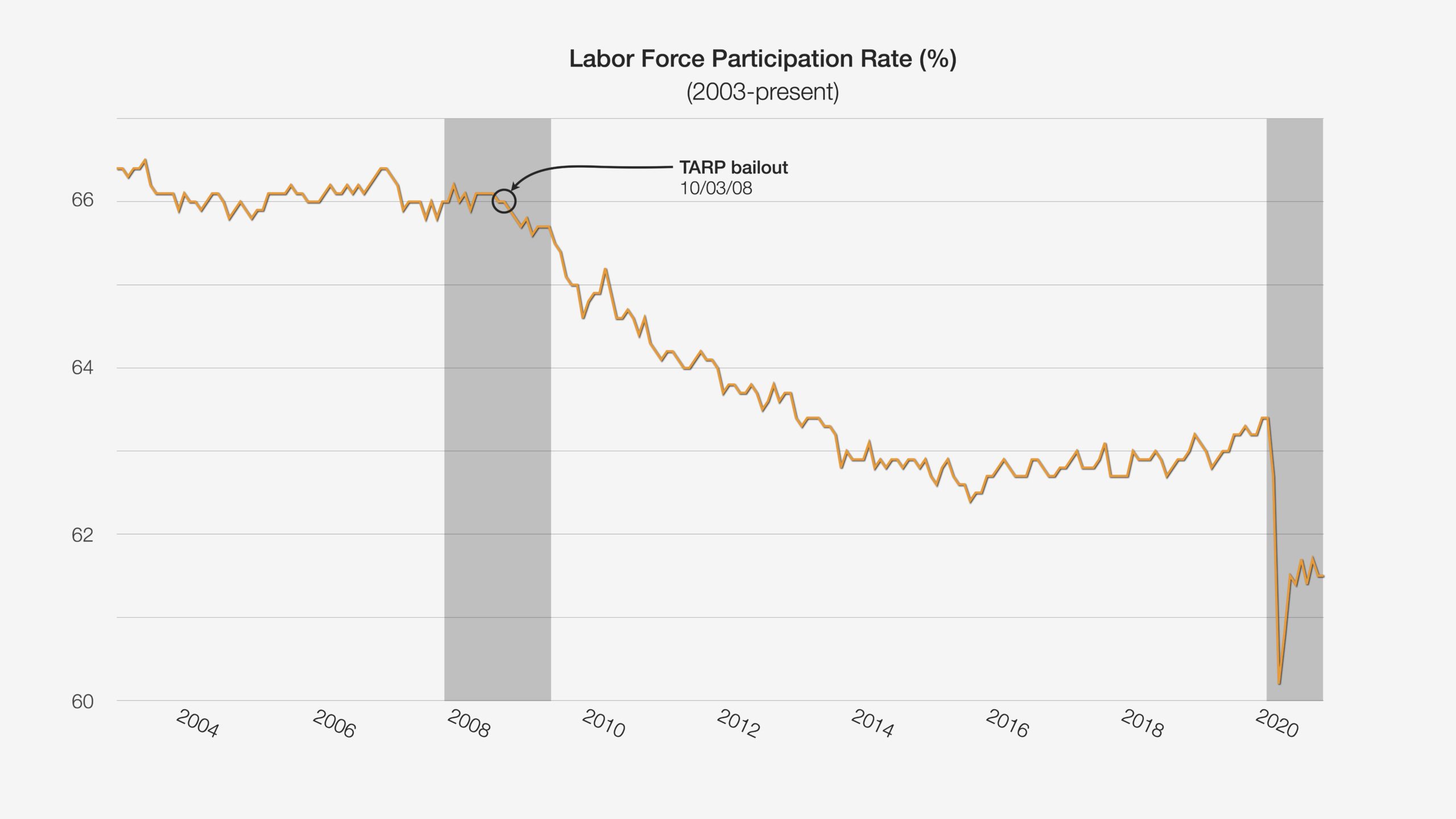

In 2008, the U.S. had a stark decision to make about which of two economies, and which of two diametrically opposed sets of principles, would govern the country going forward. The conflict over principles came to a boil over the TARP bailout.

At that point, the U.S. had to choose between the rule of law and the real economy, on the one hand, and the rule of man (cronyism) and the financial economy based on asset valuations, on the other hand.

As everyone knows by now, the U.S. chose cronyism over the rule of law and chose financialization (bubble blowing) over real goods and services. The real economy never recovered and never will recover from that decision, as the following graph of the labor force participation rate makes clear.

Allowing financially powerful people to bail themselves out with no strings attached—no boardrooms vacated, no large insolvent banks nationalized or even broken up later, etc.—sealed the fate of the U.S. From that day forward, the inmates ran the asylum.

What had landed the country (and the world) in trouble was fraud in the financial space—in particular fraudulent mortgage-backed securities, fraudulent asset valuations, fraudulent ratings, etc.—which had set the dominoes tumbling. To bail out every bad actor was to roll out the red carpet for the worst of extremely wealthy criminals and to hand them the keys to the kingdom.

Which they promptly used to take over. Within five years, it was a matter of record that crimes on Wall Street weren’t even being investigated, much less prosecuted. (See the BestEvidence video “The Veneer of Justice in a Kingdom of Crime.”)

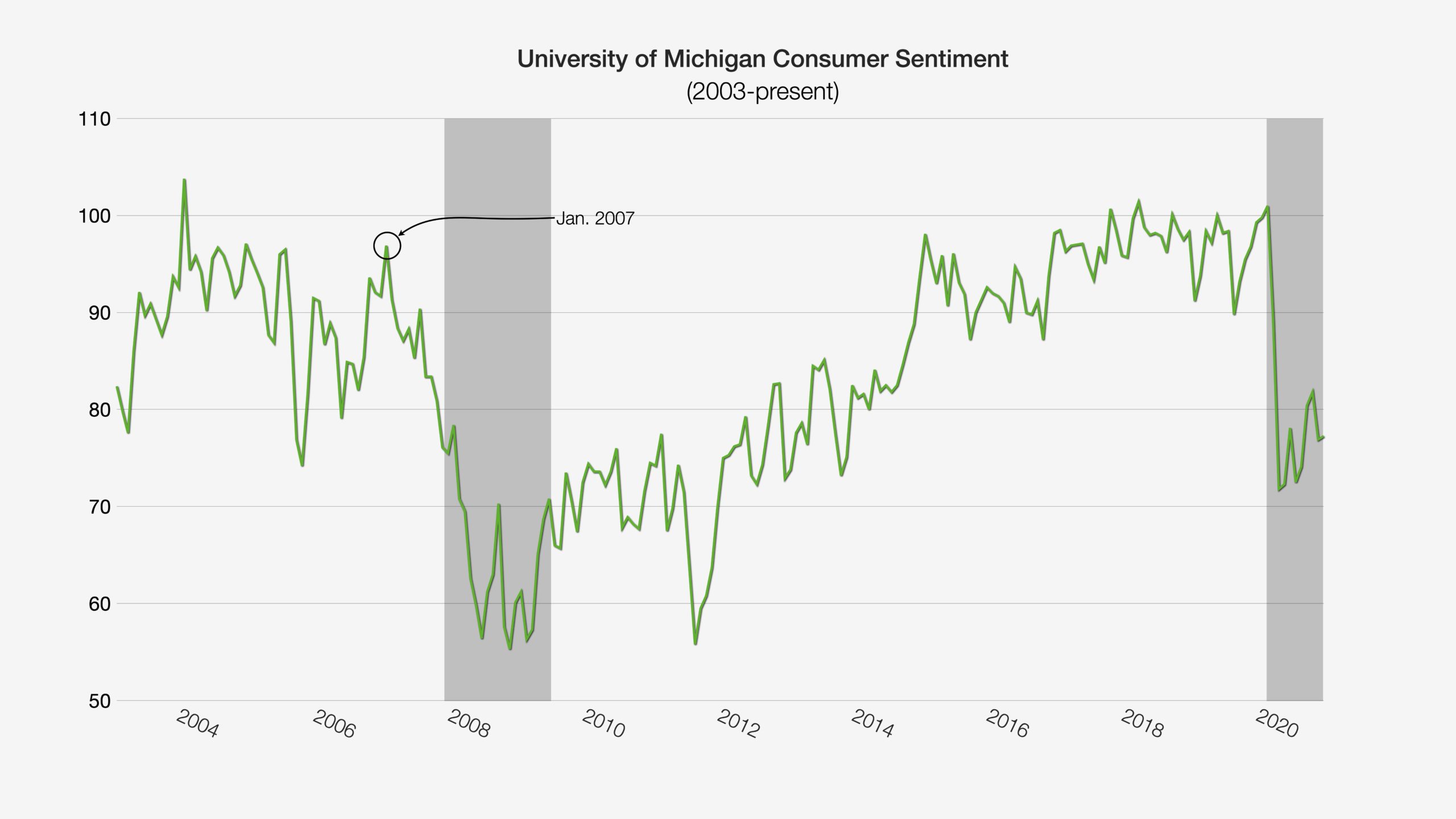

The openly acknowledged power of criminal immunity enjoyed by banks is tantamount to national suicide, as it cedes to those banks an ultimate legal power—immunity11—which cannot as a matter of law exist in a constitutional republic if in fact the law is supreme. And yet immunity does exist, and does so in the bright light of day. What doesn’t exist, therefore, is a constitutional republic observing the rule of law. Those things are all gone, as are real markets. As but one consequence, we don’t have downturns now. As Catherine puts it, we now have turn-downs instead, as vividly illustrated in this graph, “University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment, 2003-present”:

In the old days (before laws passed by legislatures were replaced by corporate decrees), consumer sentiment was a leading indicator of the real economy. Now that the economy has been taken over by criminals and financialized, consumer sentiment isn’t leading but led—by the cabal that is picking winners and losers in broad daylight.

What’s left is a mafiacracy run by banks and associated financial institutions, which are hoovering up assets and control with wild abandon. Right now they are using U.S. Treasuries, which are backed not by gold or commercial paper but by something even better from the banks’ point of view: the full faith and credit of the United States, which is the only thing backing U.S. bonds. Why settle for gold as collateral, after all, when you can have at your disposal the full dominion of a sovereign over its people, including the right to tax and imprison as well as seize property?

What has transpired over the last dozen years is nothing short of the reversal of the American Revolution, when a criminal king—the rule of man—was “thrown off” (as the Declaration of Independence had it) and replaced with the rule of law,12 which found expression a few years later in a constitution.

Don’t think for a minute that this historical pivot is lost on the current powers that be. BlackRock’s follow-up to its “going direct” plan is indeed entitled, “Policy Revolution.” Published in June 2020, and featuring the same four BlackRock authors as the “going direct” plan, “Policy Revolution” provides express “guidance” that freely discusses extending the going direct plans to include “unprecedented” control over monetary and fiscal policy, including the use of government power to impose austerity conditions, and it does so in language that would make a garden-variety dictator blush:

There are three main aspects to this revolution. First, the new set of policies are explicitly attempting to “go direct” – bypassing financial sector transmission and instead finding more direct pipes to deliver liquidity to households and businesses. Second, there is an explicit blurring of fiscal and monetary policies. Third, government support for companies comes with stringent conditions, opening the door to unprecedented government intervention in the functioning of financial markets and in corporate governance.

The never-ending pandemic (including sequels and spinoffs that one should expect of any respectable TV production) provides the perfect vehicle to carry out BlackRock’s reverse revolution. The only real question will be how that is achieved.

H. The Road Ahead: Central Bank Digital Currencies

Based on the quote above, the austerity measures contemplated by BlackRock’s “policy revolution” are by the terms of that document attached to “government support.” That support, in turn, comes from “more direct pipes to deliver liquidity to households and businesses.” This is the ultimate outcome of BlackRock’s “going direct” plan: controlling both the population and the economy through money pipes with valves that open and close in accordance with whatever “stringent conditions” the money supplier chooses to impose.

But how would such a nightmarish monetary control system even be possible? The answer is central bank digital currencies (CBDCs), as the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF’s) “Cross-Border Payments—A Vision for the Future”13 online symposium in October 2020 made clear. There, four panelists, including Agustín Carstens (General Manager of the Bank for International Settlements) and Jerome Powell (Chairman of the Federal Reserve), discussed the framework for CBDCs. Importantly, both men emphasized that CBDCs were a “national decision” and represented the third type of liability on a central bank’s balance sheet (the first two types of liabilities being cash and reserves).

The significance of CBDCs being a “national decision” is that money creation is a sovereign power. In the U.S., legal authority for the exercise of that power is found in Article 1, section 8, clause 5:

Congress shall have Power… To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin, and fix the Standard of Weights and Measures

Thus it appears that the central bankers understand that congressional approval will be needed for the Federal Reserve to issue CBDCs to people and businesses, because CBDCs are, legally speaking, equivalent to cash: like cash, CBDCs would be a liability on the Fed’s balance sheet. The corresponding asset would in all likelihood be a U.S. bond—debt—and therein lies the hook for central bank control over CBDCs—control that central banks lack over physical (i.e., non-electronic) cash.

Carstens shared his views on CBDCs by comparing them with cash:

There is a huge difference [between cash and CBDC] there. For example, in cash, we don’t know who’s using a $100 bill today, we don’t know who’s using a 1000-peso bill today. A key difference with the CBDC is that central banks will have absolute control on the rules and regulations that will determine the use that this expression of central bank liability [i.e., money], and also we will have the technology to enforce that.

Carstens later provides a very telling clue as to what “rules and regulations” he means—and to be sure, they are not rules and regulations like those passed through any constitutional process but rather the sort of “rules” that come out of corporate boardrooms in closed-door sessions:

The degree of control [with CBDCs] will be far bigger. This I think is good news. It really provides the ground to think, how can we use CBDC to really obtain these higher objectives of facilitating payments internationally; how are we going to make them to reduce costs; to enhance inclusion; how are we going to make this run smoothly?

Under Carstens’ plan, a person who is trying to use a CBDC to buy goods and services is free to do so only if he’s spending that money on things that are deemed acceptable by the private central bankers in charge that day.

That’s a breathtaking thought, contrary to any number of our fundamental notions about money, and yet there it is sitting on the table, placed there out in the open by the head of the BIS himself in October 2020.

Now, to be sure, Jerome Powell, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, did in his very reserved way express the importance of law and the need to proceed with caution in moving to CBDCs. At the same time, however, everything about Powell’s presentation—including the proceed-with-caution note he sounded—indicates that the move to CBDCs is very much a “GO” insofar as the U.S. Federal Reserve is concerned. The only real question is what the Fed’s move to a CBDC will look like.

BlackRock’s “policy revolution” provides a very disturbing clue: “stringent conditions” that “open[] the door to unprecedented government intervention in the functioning of financial markets and in corporate governance.”

In the CBDC space, then, the Fed will of course be a monopolist—at least for the time being. What the Fed is proposing (together with other central banks) is to issue CBDCs directly to people, who unlike now will have accounts at the Fed. As mentioned, CBDCs would thus represent the third type of liability on the Fed’s balance sheet; the other two being (physical) cash and (digital) reserves. The asset matching those liabilities will be one or more U.S. bonds.

Nowhere in this formulation does one see commercial banks, which have indeed been cut out altogether—at least insofar as money creation is concerned. All of the CBDC money would be created by the Fed. Commercial banks would thus function as financial intermediaries, connecting suppliers of pre-existing money with borrowers in, for example, payment transactions (albeit in CBDC, which will be created and issued exclusively by the Federal Reserve).

Commercial banks, in other words, would be ceding their money-creating powers to the Federal Reserve in a system of CBDCs. Instead of individuals getting loans from commercial banks in return for new bank deposits, which is the money-creation system in place right now, it would be the nation of CBDC users getting one big meta-loan (or several) from the Fed, which would disburse that single loan asset into millions of corresponding liabilities in the form of CBDCs, and disburse it in accordance with “stringent conditions” and “higher objectives.”

Why does the takeover of money-creating power from commercial banks matter? Because the dynamic set forth in the CBDC creation scenario—in which the Fed takes over the power of money creation from those banks—can be just as easily replicated on the next rung up the CBDC ladder: the BIS will eventually issue its own reserve currency, at which time it can do what the Fed is proposing to do now itself, and use its reserve currency leverage to take money-creating power away from the Fed (and by extension the U.S. dollar) in the same way that the Fed is proposing to use CBDCs to take over U.S. broad money supply creation from commercial banks. The latter process has already begun, as the Fed’s asset purchases throughout 2020 demonstrate.

In broad strokes, the ultimate move to abandon the U.S. dollar was telegraphed by Mark Carney, Governor of the Bank of England, in 2019: “The world’s reliance on the U.S. dollar won’t hold and needs to be replaced by a new international monetary and financial system based on many more global currencies.”

When that happens, it will formalize the end of the U.S. dollar as the world reserve currency as well as the end of U.S. sovereignty. In large part, the de facto giveaway of U.S. sovereignty occurred in 1913, when commercial banks and the newly created Federal Reserve formally took over the money-creating power found in Article 1 of the U.S. Constitution with the passage of the Federal Reserve Act. The issuance by the BIS (or equivalent) of a worldwide digital currency will mark the de jure end of U.S. sovereignty, at which point the U.S. will cede her sovereignty and revert as a matter of law to her status as a colony, subject to the whims of unaccountable figures abroad.

That story is still writing itself as we speak.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Coming into this project, I’d already made one lengthy video and was close to finishing another14 that set forth the novelty of what the Fed was doing during the pandemic, that is, using its power of reserves creation to force the mirror image creation of new bank money by commercial banks. But I hadn’t yet sat down and carefully read BlackRock’s “going direct” plan from August 2019. I’d seen the cover, and that sufficed to make me stay away. It looked too much like an assembly line emission from the policy committee at some global law firm, constructed of English words, sentences, and paragraphs but entirely indecipherable.

But Catherine encouraged me to read it, and when I did my jaw fell open: what I saw there was the exact blueprint for what the Fed had done during the pandemic, only that blueprint was dated months before the pandemic arrived.

That was my “holy shit” moment on this project, that flashpoint where the muse snaps her fingers and the 1000 tiles that you’ve been staring at for weeks jump into a brilliant mosaic that you will then devote the rest of the project to writing about. For me, every project has one of those, but until it comes you just sit there and scratch your nose and wait.

When it happens, everything suddenly makes a lot of sense. For example, you can trace the Fed’s implementation of the going direct plan (i.e., buying assets with reserves in such a way that it forces the creation of an equal amount of bank money in the real economy) back to about February 2, 2020. And when did Bill Dudley come on Bloomberg TV to explain that reserves don’t “leak out” so as to enable the purchase of stocks (which is what the Fed started doing on February 2)? That would have been January 29, 2020.

If I’ve learned anything in the seven years I’ve been making videos about the mafiacracy, it’s that everything is scripted. Yeah, they’re gonna make mistakes in execution, and that’s where you’ll get your valuable admissions, but what they do is very much part of a plan. Timelines are a big help in seeing what’s up; so are graphs.

The pandemic is no different than any other major event in our mafiacracy. I hope its function as a monetary event is clear by now, as well as the ultimate goal of total control through a digital monetary system, which is coming.

We’ll have to figure out how to counter that plan another day. In the meantime, allow me to share an insight by Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., the famous American jurist of the early 20th century:

Even a dog knows the difference between being tripped over and being kicked.

We’re now being kicked literally to death. At this point, I would be extremely careful of anyone who persists in denying that what’s going on is intentional.

Related Reading:

Larry Fink’s 2019 Letter to CEOs: Profit & Purpose

2020 Midyear Outlook The Future is Running at Us

Blackrock Investment Institute Davos Brief

Blackrock Investment Institute Davos Brief PDF

Endnotes:

1 See “The Federal Reserve – Kicking People When They’re Down” (BestEvidence, April 10, 2020) for proof that all 12 banks are private. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LPRMdCSFI8E.

2 See generally: Martens, Pam, and Russ Martens. “BlackRock authored the bailout plan before there was a crisis – now it’s been hired by three central banks to implement the plan.” Wall Street on Parade, June 5, 2020. https://wallstreetonparade.com/2020/06/blackrock-authored-the-bailout-plan-before-there-was-a-crisis-now-its-been-hired-by-three-central-banks-to-implement-the-plan/

3 To help readers understand what makes BlackRock’s plan so novel, we’ve included in this Wrap Up a “Companion Primer on Our Debt-Based Monetary System.”

4 The “going direct” plan is a policy paper and can be found at https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/literature/whitepaper/bii-macro-perspectives-august-2019.pdf.

The BlackRock authors are Stanley Fischer (former Vice Chairman of the Federal Reserve), Philipp Hildebrand (former head of the Swiss National Bank [SNB]), Elga Bartsch (current member of the European Central Bank Shadow Council) and Jean Boivin (former Deputy Governor of the Bank of Canada). The latter three authors are all high-ranking members of the BlackRock Investment Institute, which according to BlackRock’s author biographies “leverages BlackRock’s expertise and produces proprietary research to provide insights on the global economy, markets, geopolitics and long-term asset allocation – all to help clients and portfolio managers navigate financial markets.” BlackRock followed up its “going direct” plan with a second paper entitled, “Policy revolution”; see section G (citing https://www.blackrock.com/corporate/literature/whitepaper/bii-macro-perspectives-june-2020.pdf).

5 This parallel creation of new bank money along with new reserve money had not occurred under the 2008 QE program, as “The Fed’s Silent Takeover of the U.S.” (BestEvidence, August 12, 2020) makes very clear. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U_A4wUXlVAM.

6 “I think we’re looking at a V-shaped recovery in the stock market, and that has almost nothing to do with a V-shaped recovery in the economy.” The two very different fates for different segments of the economy under the pandemic and attendant lockdowns, Cramer says, have amounted to “one of the greatest wealth transfers in history.”

https://www.cnbc.com/2020/06/04/cramer-the-pandemic-led-to-a-great-wealth-transfer.html

7 The peak lending rate shown in the chart is “only” 5.25% because the numbers in the chart are averages. The actual (instantaneous) peak was 10%. https://www.cnbc.com/2019/10/23/fed-repo-overnight-operations-level-to-increase-to-120-billion.html

8 Of course, billionaire wealth grew even more as the Fed continued buying assets. “The wealth of 643 of US’ richest billionaires rose from $2.95 trillion to $3.8 trillion between March 18 and September 15, a report by the Institute for Policy Studies and Americans for Tax Fairness said.” https://markets.businessinsider.com/news/stocks/us-billionaires-wealth-net-worth-pandemic-covid-billion-2020-9-1029599756

9 The Fed had created three other programs before March 23, but all three of these were on their face intended to benefit large financial institutions.

10 When, for instance, the New York Fed creates $1000 of reserves for non-bank program recipient X (PRX), the Fed credits $1000 (via the program facility) to the reserve account of Commercial Bank Y (CBY), which books that as a new $1000 asset. CBY then creates a matching $1000 account entry in PRX’s account, which is booked as a new liability.

11 See Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England, which brilliantly encapsulates the ultimate power of a sovereign as follows: “The king can do no wrong.” That’s the United States in a nutshell, where the banks can do no wrong.

12 For a thoroughly outstanding explanation of the rule of law, see “Glenn Greenwald at Yale Law School – ‘With Liberty and Justice for Some,’” March 11, 2013: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MRiQ0SGJ_98

13 International Monetary Fund. “Cross-Border Payments—A Vision for the Future.” Panel with Kristalina Georgieva, Ahmed Abdulkarim Alkholifey, Agustín Carstens, Jerome Powell, and Nor Shamsiah Yunus, October 19, 2020.https://meetings.imf.org/en/2020/Annual/Schedule/2020/10/19/imf-cross-border-payments-a-vision-for-the-future

14 “The Fed’s Silent Takeover of the U.S.” (BestEvidence, August 12, 2020) and “Quantitative Easing Is the Biggest Sham Ever” (BestEvidence, December 17, 2020).